I would’ve been excited about any Zelda trailer, especially since I hadn’t heard about the new game. But after watching, this one had me excited for a new reason.

You see, I’ve been reflecting a lot lately on why some people are interested in nature, why others aren’t, and how it can all be explained by video games.

| Here we are in October 2013, getting ready to go to the 25th Anniversary Symphony in Grand Rapids, MI. | Hear me out. This idea struck me a few months ago, while I was reading the book Wild Ones by Jon Mooallem. In it was a passage about Satoshi Tajiri, a boy growing up in 1960s Japan collecting bugs. As the urban sprawl of Tokyo consumed his countryside, he found himself forced indoors, spending more and more time at the arcade. Jon Mooallem writes, of Tajiri: “So, in the nineties, he designed a Nintendo game that tapped into his childhood impulse for bug hunting—a virtual world, bursting with fictional biodiversity. It now contains more than 640 precisely named ‘species’ of critters, all of them waiting to be collected and traded with friends. Tajiri’s game is Pokémon.” |

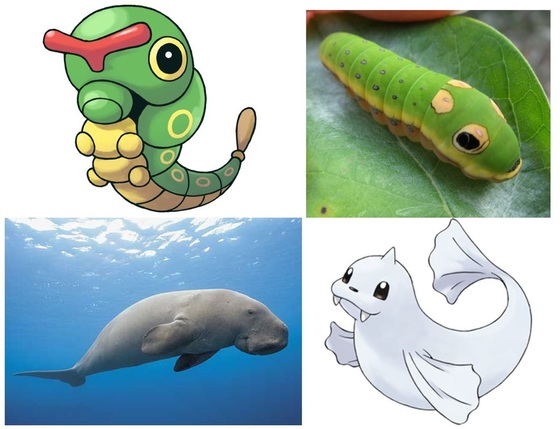

Mooallem also mentions a study that found “a typical eight-year-old in Britain can identify upward of 120 different Pokémon species, but only fifty different real plant and animal species native to his or her area, like oak trees or badgers.” This was definitely true for me as a child. My friends and I always took great pride in the fact that we could name all 150 original Pokémon (bonus if you knew the Pokérap), yet I couldn’t identify a single bird song until I was 19 and halfway through a bachelor’s degree in Environmental Studies. (Thanks, Dr. Harper.)

I think that “childhood impulse for bug hunting” is very real, and very important to this story.

| Pokémon would be significantly less fun if you never knew what anything was. People, especially kids, wouldn't have the patience for that. (Source, edited) | What I propose is that the difference between the kids who grew up to be naturalists and the kids who grew up to be video gamers comes down to the availability of information. Children are born curious, and will gravitate to places where they can get more information. In Pokémon, when you find a new creature, the game tells you about it (check out this clip of the Pokédex in action). You quickly learn all their names, which ones are rare and interesting, which ones are common, and which ones have special skills. With this knowledge, you can learn which Pokémon live in which habitats, and start to seek out the ones missing from your collection. |

Without mentors who know about nature, a game like Pokémon actually feeds a child's innate curiosity more than a walk outside with all these unknown and unidentifiable species.

It's no wonder children are drawn to games like Pokémon.

But are these games any better because the creatures aren’t real? What if you actually learned something about real nature by playing?

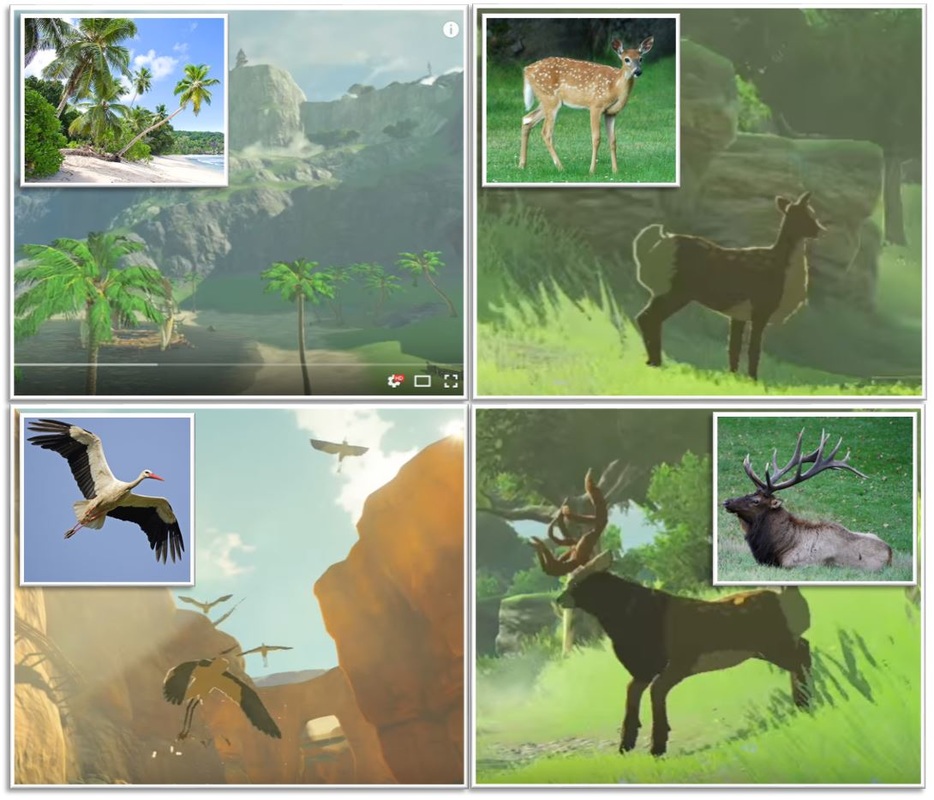

In the trailer, we first see Link (the main character) and Epona (his horse) riding through a desert canyon, and then the scene cuts to a mountainy beach with palm trees.

Except they aren’t vague video-game palms, they’re Coconut Palms. The trailer cuts again to some waterfowl that at a glance look so realistic, I paused to try to identify them. European White Storks appear. A Red-tailed Hawk screams. A Black-capped Chickadee calls. A mixed herd of White-tailed Deer and Elk graze near a trail.

This nature element is an exciting—and important—addition to the video game scene because it could begin to close the information gap that I think has kept many people from nature. When a child interacts with a deer or another real species in a game, they’re more likely to want to check it out in real life. A kid who loves lighting the Hyrulian grassland on fire just might get excited about grassland restoration ecology when they find out it involves lighting real-life grasslands on fire.

Games, of course, aren’t all bug-hunting and learning about other worlds. Games first and foremost appeal to the masses because they satisfy a desire for adventure that most people can't access in real life. Running through Ocarina of Time’s Gerudo Valley from the confines of your urban couch can feel more epic than your morning jog. But real adventure is out there, and as far as I can tell, the easiest way to find it is through ecology. Browse through some seasonal field technician job postings, and you’ll see what I mean.

When you're not busy working (aka listening for birds), I recommend listening to this.