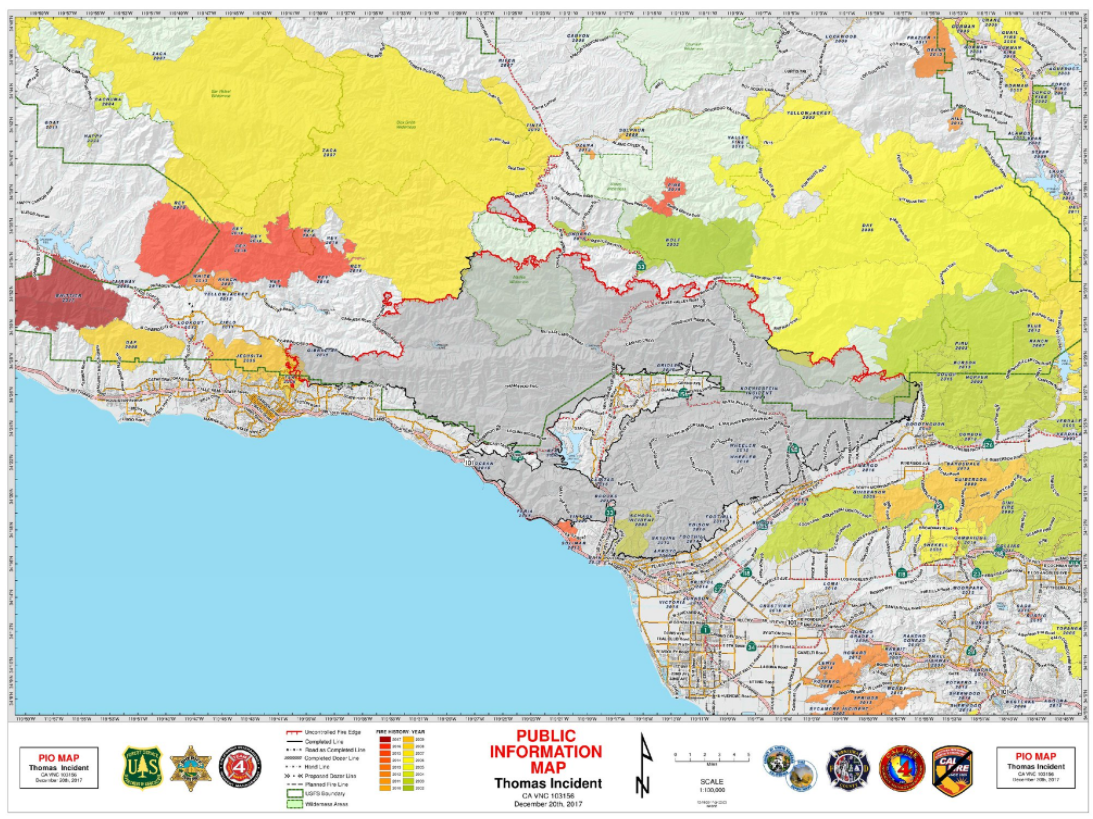

The Thomas Fire has burned through much of Los Padres Forest that hasn’t burned in recorded history. It’s reached the Zaca fire scar from 2007, but even 10 years of regrowth is plenty of time for chaparral to mature and burn. It’s generally thought that many chaparral species take 15ish years to reach sexual maturity and reproduce seeds to survive the next fire. When fires happen in rapid succession, plants don’t have time to make seeds and regenerate post-fire. Firefighters are trying to slow the westward advance and are hoping that the Jesusita and Tea fire areas that burned recently will allow for slower fire spread and more time to combat the fire front.

The fire has been halted along the western edge and has calmed down for the most part. Brave and tenacious fire crews have worked around the clock to contain the fire front and protect homes and property in the path of the flames. Unfortunately, one firefighter lost his life in the battle. I’ll be thinking of his family in the days to come. There are two different wind types that you might read about:

Santa Ana winds are intense hot winds that originate in the interior of California and blow out towards the coast. They can make a small fire turn into an uncontrollable monster in a matter of hours. They are seasonal and can be very dangerous when trying to stop an ongoing fire.

Sundowner winds are a phenomenon in the Santa Barbara region where hot dry winds will blow down the mountains of the front range in Santa Barbara. This can be really dangerous if a fire is burning in the hills as it can carry the fire right into the city.

While the winds have calmed down temporarily, there is little rain in sight. Possibly won’t see rain until the new year! A scary prospect for firefighters and Californians alike.

Future:

It seems the high pressure system hanging over Southern California may be the new normal. This climatic pattern prevents the jet stream from dipping into SoCal and dropping much needed rain. This fall/winter weather may be a reflection of the new normal for Southern California.

Now here is November/December’s post for #ClimateChanged. As with many academics this time of year, things get a little hectic towards the end of the semester/quarter.

To start us off, I wanted to lay out my thoughts behind using the term “Climate Change” vs. “Global Warming.” While they are used in different contexts and debated, they are both technically correct. Our planet, as a whole, is experiencing a rise in the average global temperature. Underneath this average change is a LOT of variation. Some areas are heating up, while others are cooling down (not many), some areas are getting wetter, some areas drier. This is where “Climate Change” comes into play. Just as different parts of the world currently have different climates (e.g Chicago vs. Sydney vs. Dubai vs. Nepal), the change in climate will differ as well. The climate is changing differently around the world. So while both terms are correct, “Climate Change” is more reflective of the variation in change that is happening around the globe.

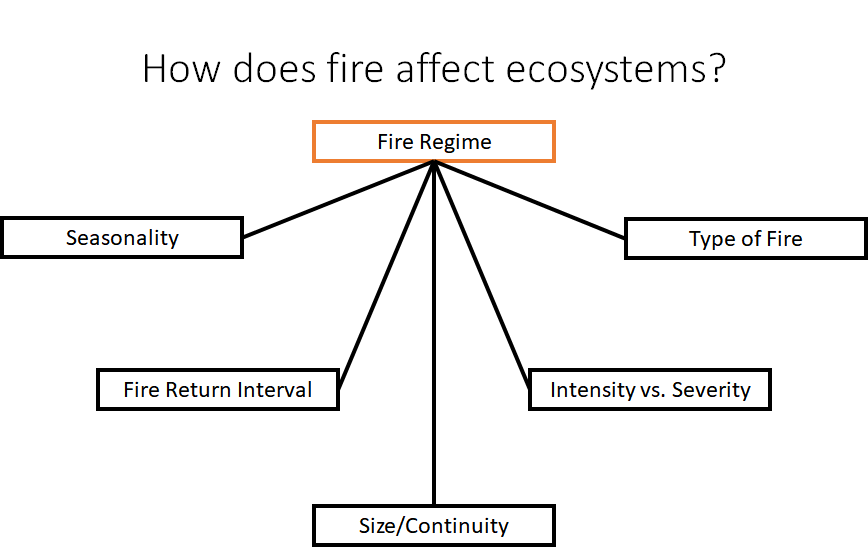

This post is an attempt to answer some burning questions about wildfires. While fires are often viewed as disastrous and a catastrophe, they can be natural events for many ecosystems around the world. California, for example, burned periodically before European settlement. Many of the plants and animals native to California are well adapted to living with wildfire disturbances. In order to better understand changes in wildfires, I want to split the conversation up into three parts. First, I want to discuss how fires interact with ecosystems, then how humans are affecting wildfires, and lastly, address Climate Change impacts.

Before we talk about how fire will change it’s important to understand how fires interact with ecosystems:

Fire Return Interval: This means how often a fire occurs in a given area/region. Frequently? Infrequently? In the link you can notice a difference in fire return interval closer to the city of Malibu...

Size/Continuity: Basically, how big do fires normally get. Some regions of the world have small fires while others can have huge fires that move across the landscape. Also, fires can occur in one big swath or can be really patchy (Figure 6), with some burned areas interspersed with unburned areas.

Intensity vs. Severity: Intensity is the amount of energy released from a fire, aka heat. You can have HOT fires and “cool” fires. Cool fires generally are associated with fires in low fuel conditions, like grasslands. Severity is debated often, but mostly refers to the amount of biomass (plants and animals) that are removed by a fire (burnt up). High severity means that a lot of things burned.

Type of fire: Different ecosystems burn differently, Surprise! You can have crown fires, surface fires, and ground fires (where the fire burns underground). Sometimes you can both in the same place. Yikes!

How are humans affecting wildfires?

As I mentioned previously, fires have been around well before human settlement. However, in recent years we have built our homes and cities closer and closer to wildlands and ecosystems that are prone to wildfires. Additionally, in some regions, we have changed the fuels (things to burn) by altering wildland ecosystems. In the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California, we prevented all fire from occurring, allowing a build-up of small trees that spur catastrophic fires. In many parts of the western US, we removed forests/woodlands in favor of non-native grasslands, which catch fire easily and spread wildfire across the landscape.

Finally, we’ve changed how fires start. Historically, ignitions in California were from lightning (rare) and Native Americans. Now we have a lot more people setting fires accidentally, and on purpose… In general, the more people living near wildlands, the more fires we experience (Figure 4). If we continue to live in fire-prone areas (also the desirable areas), we will continue to experience devastating fires. Our only option is to find some sort of coexistence. We need to fundamentally change how we think about urban development moving forward. On that note, I’m thinking about my friends in Santa Barbara and Ventura, California region right now. The Thomas fire is incredibly powerful and still on the move, stay safe!

The simple answer is: It will affect all aspects of the regime differently (not so simple of an answer…). The fire season in the United States is expanding, as are fire seasons around the world. Climate change at its core will influence temperature and rainfall. Both will have consequences for wildfires and changes to the natural fire regime. Higher temperatures + lower precipitation leads to hotter, drier fuels that can catch fire more easily. More precipitation in some areas can actually increase the amount of fuel for fires and increase the intensity of fires. This is already observed in California where some of the biggest fires occur the year after a rainy year. Lots of plant growth leads to lots of plants to burn in the next dry year.

Ultimately, wildfires are here to stay, and will likely increase in size, frequency and intensity depending on where you live. For more details there have been some excellent articles on this subject from the Union of Concerned Scientists, the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, and Scientific American. If you live near wildfire-prone ecosystems, you need to take care to reduce the likelihood of human ignitions, protect your home by not planting palm trees, and get involved with community-action plans that mitigate or cope with wildfire risk.

Cheers,

Nate